As part of compiling all of my writing in one place, this is a repost of a JVC blog post from 2020.

“I am not retained by the police to supply their deficiencies”

Sherlock Holmes to Dr John Watson, ‘The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle’

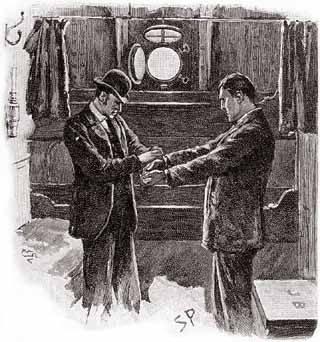

Policing remains, today, a highly contested activity of the state. It has professionalised—and bureaucratised, and brutalised—a great deal since its nineteenth-century inception, and it remains plagued by a fundamental anxiety that it is the police, not Lady Justice, are blind. This post explores the underlying mistrust of the professional police that flows from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock stories through to the detective stories being written and broadcast right now, telling us something about how we still reckon with one Victorian invention, the police force, using another: Sherlock.

It’s easy to spot a Sherlock. They possess some powerful combination of misanthropy, laser-focus and insight, and they tend to give the law-enforcement system short shrift. And these days there are many of them: ‘real’ Sherlocks, via Robert Downey Jr, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Johnny Lee Miller; reimagined Sherlocks in contemporary characters like Gregory House (House M.D.) or Detective Saga Norén ( The Bridge); and fresh Period Sherlocks like Dr Laszlo Kreizler ( The Alienist) and Dr Max Liebermann (Vienna Blood).

Sherlocks are such successful stock figures that, ironically, they dull our own powers of perception. They are the flash, eye-catching legacy of Conan Doyle’s story-telling, concealing the darker subtext of that legacy: a professional law-enforcement system that is flawed, dull, and not to be trusted to get to the truth.

The existence of the trust gap is clearest in a particular set of TV detective stories that I suggest we call the ‘extraordinary sidekick’ sub-genre. Because while Sherlock is “not retained by the police to supply their deficiencies”, that is to say, to plug the trust gap, extraordinary sidekicks precisely are.

In this sub-genre, extraordinary individuals like forger and art thief Neal Caffrey (White Collar) or ex-pretend-psychic Patrick Jane (The Mentalist) take on police work for various tenuous reasons: a deal to get out of prison (Caffrey), a personal vendetta against a Moriarty (Jane), or the thrill of more active work (as for spy-turned-criminal-psychologist Dr Dylan Reinhart in the short-lived Instinct). Whatever the circumstances, the reason that they are taken on by the “official police” is clear: criminal-justice professionals can’t even trust themselves to crack the tough cases.

A Sherlock often “shows up officialdom”, reflected in absurd or caricatured professionals who are “an obstacle to the truth”. Examples of comically poor professionals might include Sheriff Sherlock Hobbs and his Deputy, Tina Teventino, in series 2 of the Netflix series Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, or Detective Inspector Gideon Pryke, played by the wonderful Rik Mayall, in the BBC’s Jonathan Creek.

But the extraordinary sidekick sub-genre extends this sort of mistrust of criminal-justice professionals to even the best and most competent. While Holmes might “us[e him]self up rather too freely” in pursuit of Moriarty, the extraordinary sidekick is pulled along and “put … out there” by their professional partner to help solve cases they alone cannot.

Extraordinary sidekicks thus offer an odd melding of the characteristics of both Sherlock and Watson: genius detective, but acting only with a lead partner who provides their sole point of access to detective work. This both boosts and undermines the professional partner responsible for deploying them in the field. While detective fiction is “invest[ed] in the notion that the common and the trivial can be mastered-or be made to make sense-if only the proper methods are used”, the extraordinary sidekick highlights that the “proper methods” may not be those of institutionalised police forces. The extraordinary sidekick sub-genre thus turns us away from an image of institutional authority and trustworthiness and towards an interpersonal faith in law enforcement. The reciprocal relationship of trust or faith between the professional and the extraordinary sidekick they deploy becomes the only way to plug the justifiable trust gap.

See my Research page for the full version of this article was published as ‘Sherlock’s Legacy: The case of the Extraordinary Sidekick’ in Palgrave’s A Study in Sidekicks, edited by Lucy Andrew and Samuel Saunders.

Take a look at my short story collection featuring Victorian “lady detective” Meinir Davies: preorder now!

Leave a reply to Frank Tallis – Mortal Mischief (2005) – Dominique Gracia Cancel reply