Preamble

If you’re interested in reading my academic work about detective and crime fiction (free PDFs available), check it out here. Or you can take a look at my short story collection of cosy mysteries featuring Victorian “lady detective” Meinir Davies; order now!

Review

I have tended not to review here the Victorian fiction on which I write academically, outside of the research-related posts from my Great Nineteenth-Century Reading Challenge. But this was a re-read that I included in one of my annual lists, and it seemed maybe worth reviewing.

Many people have opinions about Holmes, and he lives in our collective consciousness in a way that incites the nerdier of us to want to try to explain (and often challenge) his predominance. Some people feel particularly strongly about the ‘authenticity’ or ‘faithfulness’ of any adaptations of him, like one of my own reviewers, who grumbled that my Holmes wasn’t enough like Conan Doyle’s, quite thoroughly missing the point! (That Holmes comes to us via Watson, who has his own quirks and biases in the stories, and that a Holmes who comes to us instead via a female detective relating him to yet another chronicler might turn out, well, differently……) Some people have strong commitments to a single on-screen representation. Is Benedict’s better than Robert’s, better than Henry’s? What about the traditional offerings, Jeremy Brett and Basil Rathbone, and never mind this twenty-first-century rubbish!? Anyway. You will have your opinions already, but here are mine on this particular slice of Victoriana.

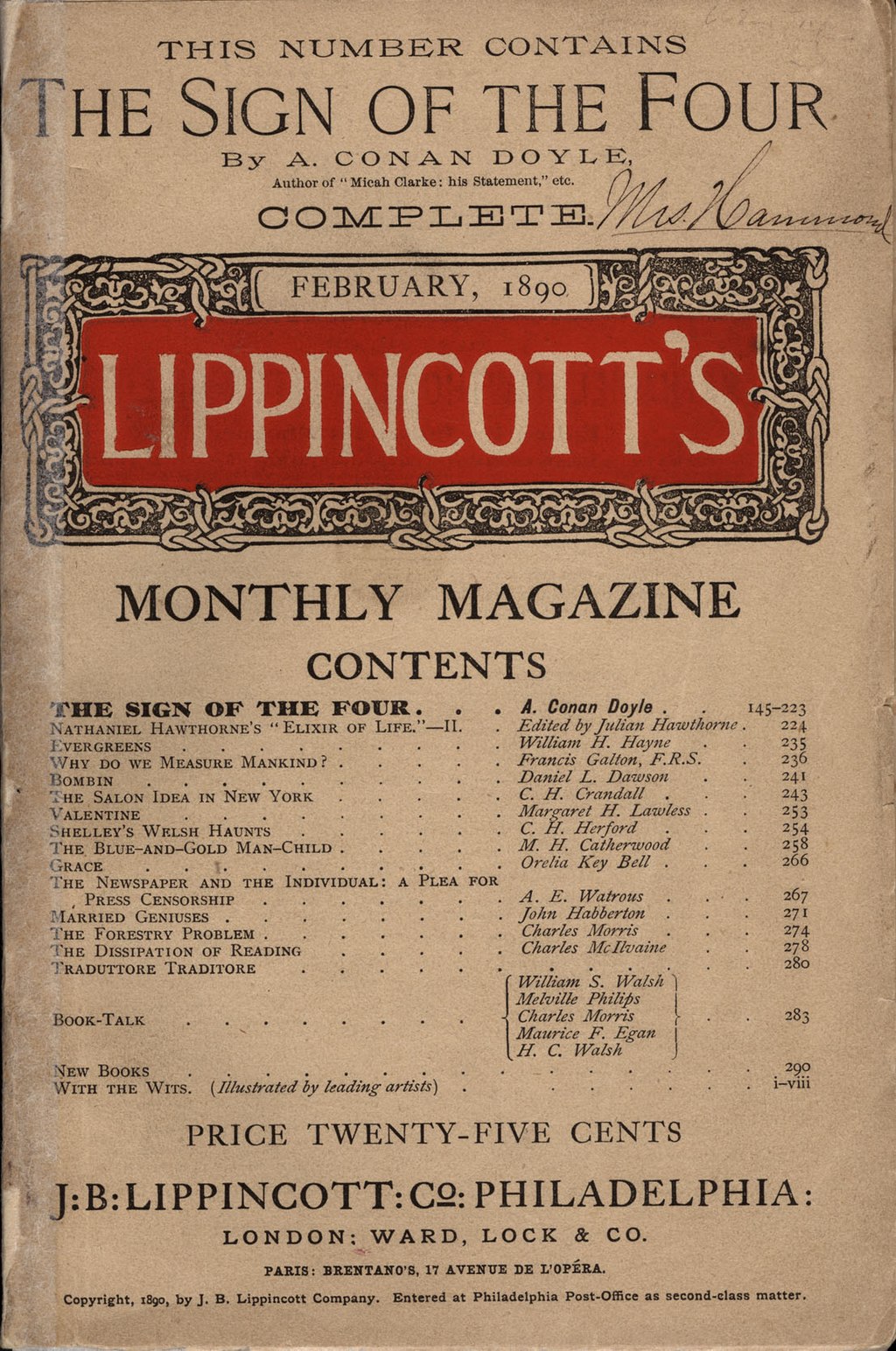

This is the second full novel featuring Sherlock Holmes, following a few years after 1887’s A Study in Scarlet, which had appeared in a Christmas Annual. Four appeared in Lippincott’s first before being published in book form, and like its predecessor it did not immediately set the world alight. It was only really in the short stories (and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in 1892) that Holmes became the eminently well-known detective that he remains today. (The original title—with its additional ‘the’—is also a little clunky, which doesn’t help, and it’s often also published as The Sign of Four.)

This is not because there is anything particularly wrong with either novel. If Scarlet introduces us to Holmes and Watson, the former’s methods and the latter’s role as the reader’s surrogate, then Four fleshes out the wider world. It is here that we encounter Mary Morstan, Dr Watson’s future wife, and Watson gets a (temporary) happy ending. (Mary dies during Holmes’ ‘Great Hiatus’, we are told, but then at least one other wife appears to crop up later on. This is a wonderful rabbit hole to dive down if you are interested!) We also get to meet the infamous Toby the Bloodhound, for those who enjoy spotting the various iterations of the pup across the Holmesian multiverse!

While Scarlet focuses on the New World and an American mystery, Four has its centre of gravity far to the east, in India, and the 1857 rebellion (sometimes called a ‘mutiny’) against British colonial rule. For many Victorianists today, the history here is the most interesting part. The 1857 rebellion led to the end of the East India Company‘s dominion over India, but not the British’s. Power was transferred to the monarchy, and Queen Victoria had been Empress of India for over a decade by the time Four was written and published. In this regard, then, Four‘s story of British and Indian heroism and thievery is a fascinating contemporary portrait of the country’s relationship with India and how it (like America) could make or break fortunes.

The central murder of Bartholomew Sholto at his imposing residence, Pondicherry Lodge, is only a precipitating event for uncovering the whys and wherefores of an assortment of related crimes and small mysteries. As a murder mystery, Four borrows somewhat from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue almost 50 years before, but the outlandishness is certainly forgivable, and there is a shoot-out not out of place in a modern context.

This is a Holmes story that hasn’t always been adapted effectively, however. Of some of the most recent, Sherlock & Co‘s 10-part podcast version had some really interesting innovations (e.g. on the character of Mary) but the travel was rather mawkish, and it really didn’t need to be that long. Meanwhile, Sherlock‘s ‘The Sign of Three‘ stretched credulity a little more with the character of Mary and fell, in some ways, into its own hype, but did some interesting things with Major Sholto. I certainly think that for this particular story the original is rather more effective and interesting than its reboots.

Take a look at my short story collection featuring Victorian “lady detective” Meinir Davies; order now!

Leave a comment