Preamble

If you’re interested in reading my academic work about detective and crime fiction (free PDFs available), check it out here. Or you can take a look at my short story collection featuring Victorian “lady detective” Meinir Davies; preorder now!

See also

These lists capture other detective/crime stories and characters that I thought of as I was reading this piece. I won’t explain why, to avoid spoilers, but they’re associations and not ‘if you liked this, then you’ll love…’ recommendations!

- SSHG fan-fiction

- Game of Thrones and the relationship between The Hound and Arya Stark

- Brittany Cavallaro’s YA series beginning with A Study in Charlotte

- Enola Holmes

- The Knick

Review (3.5 out of 5)

It took me several goes to finish this book; my hold on the Libby app timed out twice, but I waited patiently until the next reader was done to pick up the story again. This is a popular book at the start (although not quite the start) of an impressively long-running series by Laurie R. King, and I really wanted to like it, both as a reader making my way through it but also as a Sherlock scholar.

The first third felt particularly slow to me, but I kept on because there is much to appreciate and digest in this novel as a study in Sherlockiana. I haven’t read the initial book of the series, The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, and I would go back to read through that (or, more likely, track down and listen to the BBC radio adaptation!), as well as reading deeper into the series, as it is still going strong. But there were moments of endurance reading, as well as reading for pleasure. On the other hand, I did find it more engaging and interesting than the first Enola Holmes film, which has some similar themes to this novel. There was a much more robust understanding of the history, as well as appreciation of the Holmes canon, here. And there was also far less mansplaining than in the Moffat/Gatiss Sherlock 2016 Christmas Special that also covered similar ground (The Abominable Bride)!

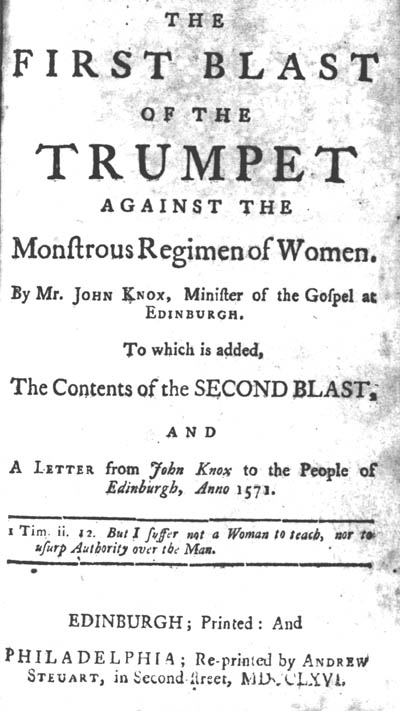

The novel draws its title from John Knox, a C16 priest/minister who was very against female monarchs and, more broadly, female anything! I recall John Knox principally thanks to a few rounds of pandemic tutoring I did with GCSE students who were missing large chunks of regular schooling when schools were shut here, and if we read him when I was a teen doing GCSE English Lit (or, indeed, in any of the Shakespeare classes I did during my undergraduate degree), I had entirely deleted him from my memory banks.

I found some of the tropes here a little hackneyed, such as Mary’s romps around London dressed as a man. This was hardly that subversive, even in Arthur Conan Doyle’s time; this is precisely how the wonderful 1860s Ruth the Betrayer penny dreadful begins, with the female protagonist storming about in male dress that almost but doesn’t quite deceive. I also found the characterisation of Mary and her relationship-building with Holmes somewhat tiresome; there was lots of mentions of verbal ‘skirmishes’, for example, that felt to me like a well-worn way to feign equality between the two main characters in service of their romantic alliance later on. Holmes himself I found characterised effectively, and his particular admiration for the armed forces and military service reminded me of some great scholarship about the Holmes stories in the context of the British Empire and Conan Doyle’s own attitudes.

There is also something somewhat uncomfortable now, as a (mid?) C21 reader, about the romantic relationship between Holmes and Mary, having met when she was 15 and he was 54. I suspect we are now more sensitive to these sorts of things than in 1995, and perhaps the novel holds up least well here.

What I found more interesting than the Sherlock/Mary marriage sub-plot was the treatment of substance abuse and addiction recovery—for Holmes, for his son, for Lt Miles Fitzwarren, and for Mary—and the characterisation and plotting around Margery Childe, the ambitious political speaker and feminist around whom the main mystery is built. There were echoes here of Margery Kempe, a C15 British mystic, considered by some to be the first author of an autobiography in English. As the novel’s title implies, the issue of female interpretation of religious scripture is a central one; Margery and Mary within the novel undertake this task, just as Margery Kempe did centuries before. I would definitely re-read this novel again to explore this as an academic interest, but sadly not for its own pleasures as a read.

If you enjoy neo-Victorian detective stories, take a look at my short story collection featuring Victorian “lady detective” Meinir Davies; preorder now!

Leave a comment